Introduction

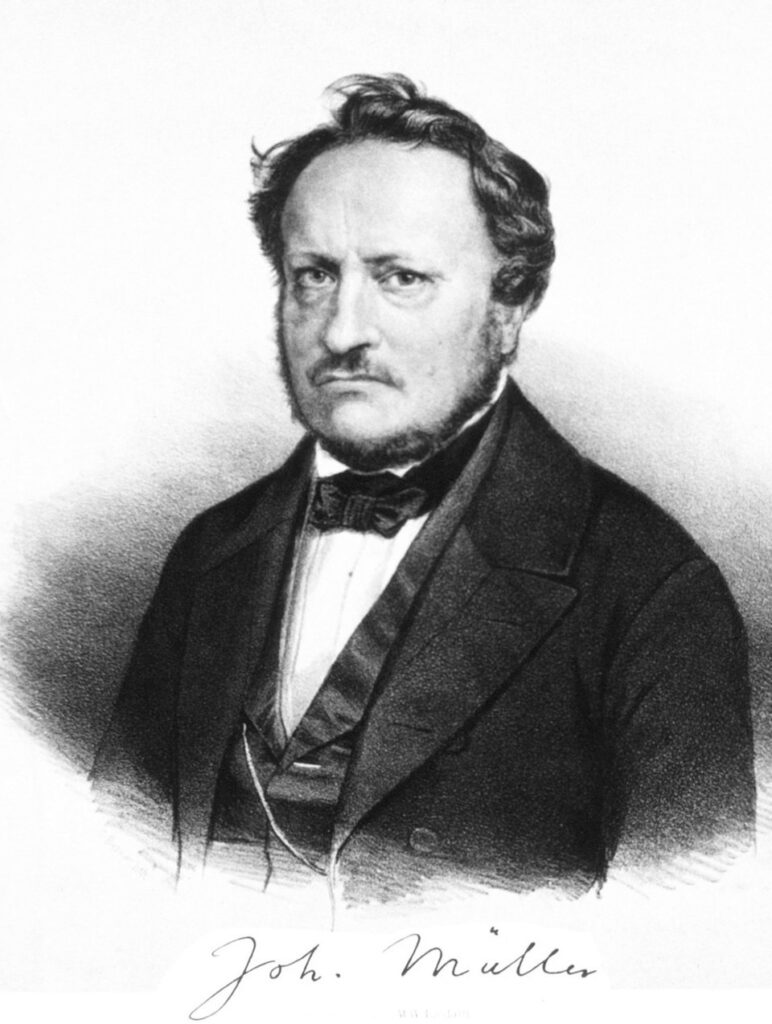

Johannes Peter Müller (1801–1858) is often regarded as the “father of modern physiology” for his role in transforming biology and medicine from speculative philosophy into a rigorous experimental science. His achievements span several disciplines, including neurophysiology, embryology, and comparative anatomy. Between 1833 and 1840, he published the Handbuch der Physiologie des Menschen (Handbook of Human Physiology). It became the definitive textbook for the 19th century, synthesizing all known knowledge of chemistry, physics, and anatomy as they applied to the human body. There were some earlier experimental physiologists, particularly William Harvey (1578-1657), the discoverer of the blood circulation, but as a broader school modern physiology started in the 19th century.

Müller’s scientific method pushed the field away from “Naturphilosophie”. This philosophical school was popular in Germany at the time and saw nature as an organic whole with a “vital force”. Its members derived knowledge from reasoning not experimentation. Müller and his pupils moved physiology toward evidence-based experimentation. Müller was an excellent mentor and trained many of the preeminent scientists of the 19th century, including: Hermann von Helmholtz (1821-1894) , Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902, The father of modern pathology), Theodor Schwann (1810-1882, Developer of Cell Theory), Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919, The father of developmental Biology), Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke (1819-1892), Albert von Kölliker (1817-1905, discoverer of mitochondria) and Emil du Bois-Reymond (1818-1896, The father of electrophysiology).

William Sharpey (1802-1880) and later Michael Foster (1836-1907) introduced Müllers concepts into British Physiology and trained the next generation of physiologists. In France modern experimental physiology was introduced earlier than in Germany by Francois Magendie (1783-1855), who trained Claude Bernard (1813-1878), the preeminent physiologist of the 19th century in France. Bernard had a similar international lab as Müller, mentoring many future physiologists, such as Willy Kühne, Peter Ludwig Panum, Louis Antoine Ranvier, Isidor Rosenthal and others.

Out of Müller’s laboratory developed the influential Berlin school of physiological materialism, led by Ernst Wilhelm von Brücke, Emil du Bois-Reymond, Hermann von Helmholtz and Carl Ludwig. This mechanistic school, argued that life could be explained entirely through the laws of physics and chemistry rather than a mysterious “vital force.” Carl Ludwig (1816–1895), who was trained as an anatomist, developed many of the tools and methods of experimental physiology. Ludwig was famously unselfish. He often did the bulk of the work on experiments but refused to put his name on the final papers, allowing his students to take the full credit. Because of this, he trained more famous physiologists (like Pavlov, Stirling, Bohr, Fick and Einthoven) than perhaps any other teacher in history. Henry Pickering Bowditch (1840-1911) also studied with Ludwig and brought the principles of modern physiology to the United States.

If there is one overarching principle in physiology, it is homeostasis. It refers to the ability of an organism to maintain a harmonized internal milieu. Almost all functions in physiology are tightly regulated and controlled to either adapt to physiological demands, such as exercise and/or to maintain constancy. Typical features underlying homeostasis are the oxygen saturation of blood, blood pressure, salt and water balance etc. The homeostasis principle was first formulated by Claude Bernard and further detailed by Walter Cannon (1871-1945) and Lawrence Joseph Henderson (1878-1942).

The subchapters of this history are organized in terms of processes and/or organs. Please browse through the chapters to find information relevant to you. The subchapters become visible when clicking on the History of Physiology link at the top of the page.