Much off the early work in this area was performed on frog hearts that we cannulated and either had nerves attached or not. The relevant nerves here are the vagus nerve, which decreases the heart rate and sympathetic cardiac nerves that accelerate the heart rate.

The electrical excitation of muscle tissue and the autonomous nervous system were central for the development of neuroscience because they are more accessible to experimental manipulation than the central parts of the nervous system. Many principles were first introduced using muscle tissue and the heart.

Claude Bernard (1818-1878) started to experiment with curare around 1840 and could show that it neither paralyzed the muscle nor blocked nerve conduction. However, if the point of contact between nerve and muscle was incubated with curare solution, stimulation of the nerve no longer triggered muscle contraction.

The concept of neurotransmitters was, however, not built on work on the neuromuscular junction but rather on the effects of the autonomous nervous system on the heart.

George Oliver (1841-1915) and Edward Schäfer (1850-1935) in England had undertaken the first systematic studies of the effects of adrenaline. Schäfer headed the Physiology Laboratory of University College London. They summarized the responses of different visceral organs to adrenal extracts by stating that they were identical to those seen following stimulation of sympathetic nerves. Oliver even performed experiments on his own son. When Oliver’s son swallowed a small amount of an adrenal gland extract, the diameter of his arteries decreased, and his blood pressure increased dramatically. Oliver and Schäfer also studied responses obtained from extracts from the cortex (the outer part) as well as the medulla (the core) of the adrenal gland. They reported that only extracts from the adrenal medulla increased heart rate, caused blood vessels to contract, and increased the tone of skeletal muscles.

In Germany, Johann Schmiedeberg (1838-1921) and Koppel (1869) extracted muscarine from the mushroom Amanita muscaria and demonstrated that it caused slowing of contractions of cardiac muscles.

John Newport Langley (1852-1925) extended the experiments of Oliver and Schaefer, also concluding that “in many cases the effects produced by the adrenal extract and electrical stimulation of the sympathetic nerve correspond exactly.” Stimulating the vagus nerves and other nerves in the craniosacral (parasympathetic) division of the autonomic nervous system generally produced effects opposite to those obtained by the adrenal extract”. These observations would eventually lead to the first speculation that adrenaline-like chemical substances might normally be involved in the innervation of visceral organs by sympathetic nerves. He proposed the term “autonomic nervous system” in 1898, suggesting differences and opposing actions of the sympathetic and parasympathetic components.

Langley also introduced the concept of “receptors” but thought that they were substances made by the receiving tissue not the nerve ending. At the time, it was very hard to believe that tiny nerve endings would produce sufficient “neurotransmitter” (term not yet used) to cause a reaction of the target tissue.

It was not until the early 1930s that the receptor concept began to gain wider acceptance. This was largely due to the work of Edinburgh pharmacologist Alfred Joseph Clark (1885-1941), which enabled him to determine that drugs are generally effective only on the membrane that surrounds a cell. Moreover, by a brilliant quantitative analysis, Clark was able to conclude that drugs do not act on the entire cell membrane, but on discrete receptor units embedded in the cell membrane.

Thomas Renton Elliott (1877–1961), working with John Langley, is commonly given credit for being the first to suggest the existence of chemical neurotransmitters and to suggest the term. He reported that at virtually all visceral organs the effect of adrenaline was identical to that produced by stimulating the corresponding sympathetic nerve, resulting in the statement “Adrenaline might then be the chemical stimulant liberated on each occasion when the impulse arrives at the periphery.” However, he and Langley believed that the muscle produced the adrenaline, not the motor neuron.

Walter Dixon (1871–1931), a leading figure in British pharmacology, shortly after suggested that a humoral factor (muscarine-like) was secreted by the vagus nerve, the parasympathetic nerve that innervates the heart. He believed that the heart contained a precursor of a substance that slowed down the heart upon activation of the vagus nerve. Reid Hunt (1870-1941), an American pharmacologist working at the time with Paul Ehrlich in Frankfurt, reported that acetylcholine was the most powerful substance known for lowering blood pressure, a well-established parasympathetic response. But at the time acetylcholine was not considered a substance occurring in vivo.

More than anyone else, Henry Hallett Dale (1875–1968, Nobel Prize 1936) is responsible for the discoveries that provided the foundation for proving that nerves secrete humoral substances. He is also a founder of modern pharmacology. He found the first adrenaline blocking agent (ergotoxine), and this later became a basic pharmacological tool for testing for the presence of adrenaline. With the help of George Barger (1878-1939), Dale found noradrenaline to be the most potent substance in mimicking sympathetic responses. We know that noradrenaline is the neurotransmitter secreted by most sympathetic nerves, but at the time it was not known to occur in vivo, and Dale thought of it as only an interesting synthetic compound. He thought the same was true for acetylcholine. He found that acetylcholine and muscarine had the same effect at several sites. There were other sites, however, where muscarine was not effective in mimicking acetylcholine, although at these sites low doses of nicotine did mimic acetylcholine. Dale designated acetylcholine active sites as either “muscarinic” or “nicotinic,” a terminology still used today. By 1914 Henry Dale had established that acetylcholine was the most potent substance known capable of mimicking parasympathetic effects.

Otto Loewi (1873-1961) than took the next step. Loewi performed a very simple yet elegant experiment. Using an isolated frog heart he had previously found that stimulation of the vagus nerve resulted in a slowing of the heart rate, while stimulation of the sympathetic nerve caused the heart rate to speed up. He reasoned that stimulation of either the vagus or sympathetic nerve would cause the nerve terminal to release a substance which would either slow or accelerate the heart rate. To prove this, he took a frog heart, which had been cannulated to perfuse the fluid inside the heart, and electrically stimulated the vagus nerve until the heart rate slowed. He then collected the fluid of the heart and added it to a second frog heart which had been stripped of its vagal and sympathetic nerves. This was sufficient for the second heart to slow down. Loewi called the released substance “Vagustoff’, which was later confirmed to be acetylcholine and was found to be the principal neurotransmitter in the parasympathetic nervous system. He called the substance that increased the heart rate the “Acceleransstoff”, which was later identified by Ulf von Euler (1905-1983, Nobel Prize 1970) as noradrenaline. A similar experiment was carried out by Walter Cannon (1871-1945) in which he electrically stimulated the cardiac sympathetic nerves in anesthetized cats. During stimulation, they drew blood from the coronary sinus, the vein draining the heart. The collected blood was then perfused into an isolated heart preparation, which increased the heart rate.

In 1930 Henry Dale and John Gaddum (1900-1965) started to investigate whether the neuromuscular junction was also chemically mediated. They demonstrated that a skeletal muscle contracted when even a small amount of acetylcholine was injected into its vascular system. To identify the small amounts of acetylcholine released from nerve endings, a sensitive assay was required. This had been developed by Bruno Minz and Wilhelm Feldberg (1900-1993) using leech muscle and an inhibitor of acetylcholine esterase (physiostigmine). In the assay the muscle contracts in the presence of minute amounts of acetylcholine. In less than three years, between 1933 and 1936, Feldberg published twenty-five experimental papers, with Dale and with various members of the exceptional group of colleagues demonstrating that acetylcholine is secreted by many autonomic nerves. George Lindor Brown (1903-1971) in Dale’s laboratory than provided evidence that acetylcholine was also used by motor neurons.

Walter Cannon came close to discover the release of neurotransmitters from nerve terminals and confirmed the release of an adrenaline by the sympathetic nervous system. However, he got bogged down by looking for adrenaline-like substances, which were later explained by the action of noradrenaline and two different adrenergic receptors. Cannon coined the term “fight or flight” to describe the body’s acute sympathetic response to threat. He demonstrated that emotional or physical stress triggers widespread activation of the sympathetic nervous system. This work reframed emotion as a physiological event, not merely a psychological one.

It was Ulf von Euler (1905-1983) who finally was able to prove that sympathetic nerves secrete noradrenaline, using a technique developed by his Swedish colleague Nils-Åke Hillarp (1916-1965).

Nils-Åke Hillarp’s most important research was with Bengt Falck (1927-2023), as they together developed the widely known Falck-Hillarp fluorescence method. This method made it possible to transform certain monoamines, specifically serotonin and the three catecholamines dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline to fluorescent substances that could be detected on the cellular level by microscopy. Using this method, Hillarp and Falck could demonstrate the presence of these monoamines in the central as well as the peripheral nervous system with great precision and sensitivity. This became the first, and conclusive, evidence of the function of monoamines as interneuronal signal substances (transmitters). Arvid Carlsson (1923-2018), Falck and Hillarp published a study in 1962, which was based on the Falck-Hillarp fluorescence method on the cellular location of noradrenaline and dopamine in the brain, showing that noradrenaline is located in nerve cells (neurons) and functions as a transmitter. However, they could not ultimately define the cell type that harbors dopamine and were thus not able to state with certainty that dopamine is a transmitter. However, Carlsson could show that depletion of dopamine by reserpine caused Parkinson’s-like symptoms, which could be reversed by giving the precursor L-Dopa. This resulted in efforts in several countries to develop L-Dopa as a drug to treat Parkinson’s disease. Carlsson reported on a paradigm shift between a CIBA foundation symposium in 1960, where most researchers were critical about a role of catecholamines as neurotransmitters in the brain, while at a meeting in 1965 in Stockholm this was common sense.

The substance we now call serotonin was first isolated and named “serotonin” in 1948 by Maurice Rapport (1919-2011), Arda Green and Irvine Page (1901-1991). They were studying a vasoconstrictor factor in blood serum and successfully isolated and crystallized it, naming it serotonin (“serum” + “tonic”). Independently, Vittorio Erspamer (1909-1999), an Italian pharmacologist, had already discovered a substance in the gut that caused strong smooth‑muscle contraction. He named it enteramine (1935 onward). In 1952, Erspamer and B. Asero showed that enteramine and serotonin were the same molecule—5‑hydroxytryptamine (5‑HT).

Around the same time the receptor side was also investigated in more detail. In 1948 Raymond Alquist (1914-1983) demonstrated that the actions of adrenaline‑like substances could not be explained by a single receptor. By comparing the rank order of potency of six sympathomimetic agonists across different tissues, he showed that the same drugs produced different effects depending on the organ. This led him to propose two distinct receptor types: α‑adrenoceptors and β‑adrenoceptors. This was a conceptual breakthrough that reshaped autonomic pharmacology. Ahlquist’s receptor classification directly enabled the development of β‑blockers, by James Black. Black hypothesized that a form of treatment for angina pectoris would be to reduce oxygen demand of the heart rather than increase oxygen supply to it, ultimately leading to his development of propranolol, later earning him the Nobel Prize for his discoveries in 1988. Ahlquist’s method—using rank‑order potency across tissues—became a model for receptor classification.

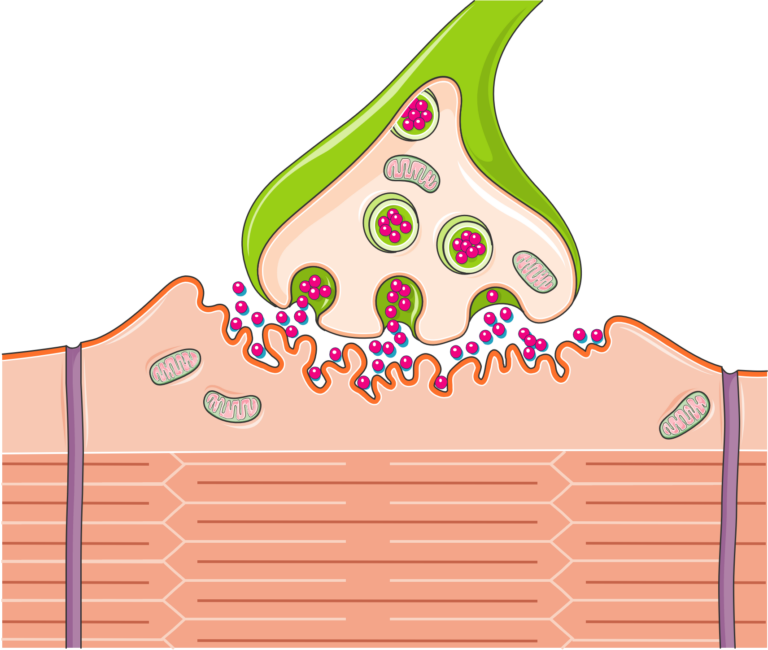

Hillarp’s and Herman Blaschko’s group (Herman Blaschko (1900-1993) German biochemist who investigated catecholamine metabolism) then established that catecholamines are stored in small vesicles in chromaffin cells, thereby establishing the role of vesicles in the release of neurotransmitters. Blaschko wondered how the catecholamines got out when nervous impulses reached the cells. Exocytosis was not among the possibilities he considered. It required the analogy of the “quantal” release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular shown by Bernhard Katz (1911-2003, Nobel Prize 1970); the demonstration of the co-release with catecholamines of other vesicle constituents such as ATP and dopamine β-hydroxylase; and the unquestionable electron microscopic images of vesicles fusing with the plasma membrane to establish exocytosis.

Bernhard Katz demonstrated that neurotransmitters—specifically acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction—are released in discrete packets, which he called quanta. This was a conceptual revolution: instead of a continuous chemical flow, synaptic transmission is probabilistic and uses packages of neurotransmitters.

Katz and his collaborators showed that calcium ions are essential for triggering neurotransmitter release. When an action potential arrives, calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal initiates vesicle fusion and quantal release.

In the 1950s, Katz measured electrical changes at the neuromuscular junction and demonstrated how acetylcholine is released in fixed amounts during synaptic transmission.

He discovered that even without nerve stimulation, muscle fibers show tiny spontaneous depolarizations—MEPPs—each corresponding to the release of a single quantum of acetylcholine. This provided the first physiological evidence for vesicular packaging.

It took a long time to establish the concept of a chemical synapse for the central nervous system. Most researchers could not envision a process fast enough to transmit electrical signals in milliseconds. By contrast Walter Cannon was asking “How can the electragonist explain the 0.2–0.4 millisecond delay that everyone agrees occurs at synapses?” A key figure in the dispute about sparks (electrical connection) and soups (neurotransmitter release) was John Eccles (1903-1997, Nobel Prize 1963), who first was the most outspoken proponent of the electrical transmission but turned from Saul to Paul after intracellular electrodes were developed and he could measure that at inhibitory interneurons an incoming depolarisation turned into a hyperpolarisation in the subsequent neuron. This allowed him to share the Nobel Prize with Hodgkin and Huxley.[1]

Walter Cannon pushed the evidence for a chemical transmission at the neuromuscular junction. He cited the example of curare, which blocked the response of skeletal muscles, but did not interfere with the nerve impulse. Curare did, however, raise the threshold of response to acetylcholine. Similarly, a small intravenous injection of eserine enhanced skeletal muscle responses to nerve stimulation although it did not alter the nerve impulse. Eserine, Cannon reminded readers, prolongs the action of acetylcholine by inhibiting cholinesterase. Such results, Cannon concluded, could be understood only by assuming that the nerve impulse is effective only to the extent that acetylcholine is active.

David Nachmansohn (1899-1983) suggested in 1936 that the electric organ of the electric ray was a good preparation to study the action of acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter because the electric organ is derived from muscle tissue. This preparation was used by Jean-Pierre Changeux (born 1936) to isolate the acetylcholine receptor in 1970, the first isolation of any membrane receptor.

Julius Axelrod (1912-2004) received his Nobel Prize in 1970 for his work on the release, reuptake, and storage of the neurotransmitters adrenaline and noradrenaline. Working on monoamine oxidase inhibitors in 1957, Axelrod showed that catecholamine neurotransmitters do not merely stop working after they are released into the synapse. Instead, neurotransmitters are recaptured (“reuptake”) by the pre-synaptic nerve ending and recycled for later transmissions. He theorized that adrenaline is held in tissues in an inactive form and is liberated by the nervous system when needed. This research laid the groundwork for neurotransmitter reuptake inhibitors.

[1] Bechtel, W. Minding the gap: discovering the phenomenon of chemical transmission in the nervous system. HPLS 45, 37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-023-00591-6

References

Bechtel, W. (2023). Minding the gap: discovering the phenomenon of chemical transmission in the nervous system. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 45(4), 37.

Changeux, J. P. (2020). Discovery of the first neurotransmitter receptor: the acetylcholine nicotinic receptor. Biomolecules, 10(4), 547.

Karim, S., Chahal, A., Khanji, M. Y., Petersen, S. E., & Somers, V. K. (2023). Autonomic cardiovascular control in health and disease. Comprehensive Physiology, 13(2), 4493-4511.

Arvid Carlsson – Nobel Lecture. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2026. Thu. 22 Jan 2026. <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2000/carlsson/lecture/>

Valenstein, E. S. (2005). The war of the soups and the sparks: The discovery of neurotransmitters and the dispute over how nerves communicate. Columbia University Press.