The concept of membranes, the membrane potential and the action potential

The cell theory that all tissues are made of cells and that cells come from cells was developed in the 19th century by Theodor Schwann (1810-1882) and Matthias Schleiden (1804-1881). This was driven by the development of compound microscopes.

Wilhelm Pfeffer (1845-1920) proposed in 1887 that cells generally were surrounded by semipermeable membrane. Charles Ernst Overton (1865-1933) then found at the end of the 19th century that fat soluble substances passed through membranes more readily than water soluble ones and concluded that membranes acted like fatty oils. In 1925 Hugo Fricke and Sterne Morse working on erythrocytes measured a membrane capacity of 0.81 μF/cm2 and suggested a transmembrane thickness of 3.3 nm, implying a monomolecular structure. That biological membranes could be made up of a lipid bilayer were first proposed in 1925 by Evert Gorter (1881-1954) and Francois Grendel. James Danielli (1911-1984) and Hugh Davson (1909-1996) added proteins to the surface of the membrane in 1935. Seymour Jonathan Singer (1924-2017) and Garth L. Nicolson (born 1943) published their landmark paper, “The Fluid Mosaic Model of the Structure of Cell Membranes,” in Science in 1972, which, with some later refinements established our current model of biological membranes.

Adolf Eugen Fick (1829–1901) was a German physiologist and physicist whose work bridge the gap between hard physics and medical science. At just 26 years old, Fick derived the mathematical laws that govern how particles move from areas of high concentration to low concentration. He based these on the analogy of heat flow (Fourier’s Law). Fick’s First Law: States that the “flux” (rate of movement) of a substance is proportional to the concentration gradient. Fick’s Second Law predicts how diffusion causes the concentration to change over time. Ficks law describes how ions diffuse down concentration gradients and how oxygen diffuses across cell membranes.

One of the first thorough studies showing electrical excitability of muscle tissue was performed by Luigi Galvani (1737-1798). He demonstrated that a discharge from Leyden jar caused the frog legs to contract. Galvani already recognized that nerve fibers must be insulated in some way to conduct electricity without loss. Carlo Matteucci (1811-1868) went a step further and demonstrated inherent bioelectricity in motor nerves.

The German physiologist Emil du Bois-Reymond (1818–1896) is often called the “Father of Electrophysiology.” His discoveries essentially turned the study of the nervous system from a branch of “vitalism” (the idea that life is driven by a mystical soul-force) into a branch of physics. In a little less than two years—from March 1841 to January 1843—he created the discipline of electrophysiology. He discovered that nerve signals are electric in nature and more precisely discovered the Action Potential, which he called the “Negative Variation”. Using a highly sensitive galvanometer that he built himself, he observed that when a nerve is stimulated, the resting electrical electric current (an injury current) momentarily drops. This proved that the “nervous principle” was not a mysterious fluid or spirit, but measurable electricity. Du Bois-Reymond discovered that even when a muscle or nerve is at rest, it maintains a constant electrical charge. He noticed that if he cut a muscle or nerve, a current would flow from the undamaged surface to the injured end. He named this the resting current. This paved the way for our modern understanding of the resting membrane potential. He coined the term electrotonus to describe the changes in the electrical properties of a nerve when an external current is applied to it. He discovered that applying a current doesn’t just stimulate the nerve at the point of contact; it alters the electrical state (polarization) of the nerve along its entire length.

During this time vitalism was a mainstream philosophy in Germany. Du Bois-Reymond famously “swore an oath” with fellow scientists (like Hermann von Helmholtz) to prove that no forces operate in living organisms other than those found in physics and chemistry (like gravity, magnetism, and electricity). In a famous 1872 speech, he argued that while science can explain almost everything in the physical world, it reaches its limits when exploring the nature of matter and the origin of consciousness. He ended his speech with the famous Latin phrase: “Ignoramus et ignorabimus” (We do not know, and we shall not know).

Du Bois-Reymond was a master instrument maker. Because the tools of his era weren’t sensitive enough to measure the tiny currents in frog legs, he invented his own: Non-polarizable electrodes: These prevented chemical reactions from interfering with electrical readings. He also developed a device used to deliver precisely graded electrical shocks to tissues. He hand-wound kilometers of copper wire to create the most sensitive electrical detectors of the 19th century.

Du Bois-Reymond did not get everything right. He believed muscles had a natural “resting” electrical current. His student Ludimar Hermann (1838-1914) proved that this “resting current” was actually an injury current. He showed that a perfectly healthy, intact, resting muscle is electrically silent.

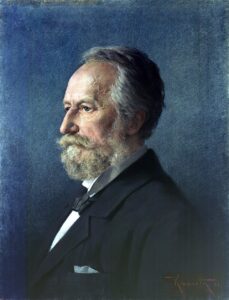

Julius Bernstein (1839–1917), another student of Emil du Bois-Reymond and Hermann von Helmholtz, is a central figure in the history of neuroscience. He is credited with transforming the observational study of animal electricity into a precise, quantitative science. His discoveries effectively settled the disputes of his mentors and provided the first biophysical model for how nerves and muscles function.

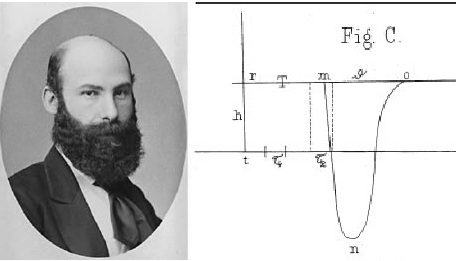

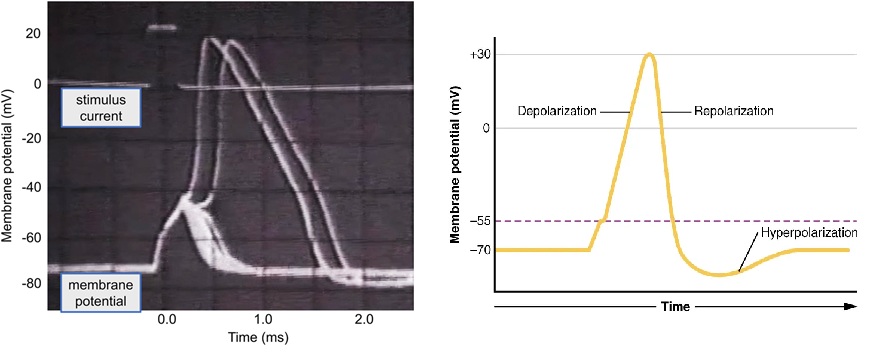

One of Bernstein’s greatest technical achievements was the invention of the differential rheotome (current slicer) in 1868. In the 19th century, electrical signals in nerves were too fast for existing galvanometers to capture accurately. The rheotome allowed Bernstein to sample tiny “slices” of the electrical event at precise intervals. By combining these samples, he reconstructed the first accurate waveform of the action potential. He measured the conduction velocity of the nerve impulse and showed that the “negative variation” (as du Bois-Reymond called it) had a specific rise and fall time, lasting about 0.5 to 1 millisecond. Herman von Helmholtz was the first to determine the speed of a nerve impulse. Bernstein’s most lasting contribution is the Membrane Theory (1902), which remains a cornerstone of modern electrophysiology. Utilizing the new field of physical chemistry (specifically the Nernst equation), he proposed that the cell membrane is semi-permeable, allowing only certain ions (primarily Potassium, to pass through at rest. Because potassium ions are more concentrated inside the cell, they diffuse outward, leaving a negative charge inside. He estimated this resting potential to be approximately -60 mV. He further hypothesized that during stimulation, the membrane undergoes a “temporary breakdown” in its selective resistance, allowing other ions to rush through and causing the voltage to drop toward zero.

Bernstein acted as the “great unifier” between the conflicting views of his teacher, du Bois-Reymond, and his rival, Ludimar Hermann. Bernstein agreed with Du Bois-Reymond that the electrical potential pre-exists in the living cell (at rest), it isn’t just an “artifact” of injury. But Bernstein adopted Hermann’s idea that the impulse travels as a self-propagating wave of electrical current from one segment of the nerve to the next.

By combining these, Bernstein proved that du Bois-Reymond was right about the source of the electricity (the resting potential), while Hermann was right about the mechanism of its propagation (the local circuit).

Later in his career, Bernstein applied his theories to the study of electric fish (like the Torpedo ray). He correctly identified that the high-voltage shocks produced by these fish were the result of the summation of many small membrane potentials from specialized cells called electrocytes, arranged in series like a battery.

While Bernstein’s theory was later refined (scientists later discovered that the action potential “overshoots” zero and becomes positive due to Sodium ions), his work provided the primary framework for neuroscience for over 40 years.

Walter Nernst (1864-1941, Nobel Prize 1920), a German physicist, developed the eponymous equation in 1887. The equation quantifies the electrical potential generated by unequal concentrations of an ion separated by a membrane that is permeable to the ion. Bernstein already used these new concepts when developing his membrane electricity model.

An accidental discovery by Edgar Douglas Adrian (1889-1977, Nobel Prize 1932) in 1928 proved the presence of autonomous electricity within nerve cells. Adrian described, “I had arranged electrodes on the optic nerve of a toad in connection with some experiments on the retina. The room was nearly dark, and I was puzzled to hear repeated noises in the loudspeaker attached to the amplifier, noises indicating that a great deal of impulse activity was going on. It was not until I compared the noises with my own movements around the room that I realised I was in the field of vision of the toad’s eye and that it was signalling what I was doing. A key result, published in 1928, was that more intensive stimuli do not result in stronger signals, but rather signals that are sent more often and through more nerve fibers.

The recording of action potentials was much refined by Joseph Erlanger (1874-1965) und Herbert Spencer Gasser (1888-1963) who shared the Nobel Prize in 1944. This was made possible by the development of amplifiers and the oscilloscope. They also classified nerve fibers into three main groups (A, B, and C) based on their diameter, myelination, and conduction velocity, which are crucial for understanding nerve function.

All electrical measurements were performed with extracellular electrodes up to this point, when John Z. Young (1907-1997) introduced the squid giant axon into electrophysiology in 1934. John Young performed research at Napoli Stazione Zoologica and described large transparent tubes of almost 1mm in diameter, which he presumed to be axons (they are syncytia of several hundreds of axons). In 1936 he convinced Kenneth Cole and Alan Hodgkin to use this preparation.

In 1939, Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley, set out to test Bernstein’s Membrane Theory and explain the shape of the action potential. Bernstein was limited by the technology of 1902. He could only measure signals from the outside of a nerve. Hodgkin and Huxley wanted to get inside, but human and mammalian neurons are microscopic. To impale a nerve, Young’s discovery of the giant axon of the Atlantic Squid (Loligo pealeii) was the ideal preparation. The giant axon is used for their jet-propulsion escape response. It is nearly 1 mm in diameter—roughly 1,000 times thicker than a human neuron. Its size allowed them to insert a tiny glass electrode directly into the nerve cell to measure the voltage difference between the inside and the outside.

Bernstein’s theory predicted that during a nerve impulse, the membrane would simply “leak,” and the voltage would drop to zero. However, when Hodgkin and Huxley recorded the first intracellular action potential, they saw the voltage didn’t just stop at zero; it became positive (+40 to +50 mV) for a fraction of a millisecond. This “overshoot” proved that the membrane wasn’t just breaking down; it was becoming specifically permeable to a different ion, namely Sodium. Using a technique called the Voltage Clamp, they were able to fix the voltage of the membrane to see which ions were moving and when. They discovered the action potential is a two-step process: First, Voltage-gated channels open, and Sodium ions rush into the cell, briefly making the inside positive (the overshoot). With a short delay, Sodium channels close, and Potassium channels open, allowing potassium ions to rush out, returning the cell to its negative resting state. Hodgkin and Huxley didn’t just describe the biology; they modelled the physics.

To this end the Nernst equation was developed by David Eliot Goldman (1910-1998), Alan Lloyd Hodgkin (1914-1998, Nobel Prize 1963) and Bernard Katz (1911-2003, Nobel Prize 1970) into the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz (GHK) voltage equation — one of the foundational tools in membrane physiology. It generalizes the Nernst equation by accounting for multiple ions and their relative permeabilities, giving a realistic estimate of a cell’s resting membrane potential. The GHK equation could be used to create a series of nonlinear differential equations—now known as the Hodgkin-Huxley Model—that can predict the electrical behavior of a neuron with high accuracy. For this work, they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1963. It took the discovery of tetrodotoxin (TTX), a potent neurotoxin commonly found in certain marine fish, which selectively blocked the Na+ current without any effect on the K+ current, to consolidate the notion of two physically separate pathways for ions in the axon.

The Hodgkin and Huxley model built on previous research by Kenneth Cole (1900-1984), David E. Goldmann (1910-1998) and Howard Curtis.

Kenneth Cole was often called the “Father of Modern Biophysics.” He was famously gracious about not receiving the Nobel Prize alongside Hodgkin and Huxley, despite his Voltage Clamp being the tool that made their work possible. Moreover David E. Goldman (1910–1998) derived the Goldmann field equation during his doctorate degree in 1943 working with Kenneth Cole.

Working at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole during the late 1930s, Cole and Curtis provided the physical proof that the cell membrane changes its properties during a nerve impulse. While Hodgkin and Huxley measured voltage, Cole and Curtis measured impedance (electrical resistance). They placed a giant squid axon in a specialized circuit and measured its conductivity while it fired. They found that when the nerve impulse passed by the membrane’s electrical conductance increased 40-fold. This was the first evidence that the membrane wasn’t just a static barrier; it was a dynamic structure with gates (ion channels) that opened to let ions through.

One of their most surprising findings was about the membrane’s capacitance (its ability to store an electrical charge). They discovered that while the resistance of the membrane plummeted during an action potential, the capacitance stayed almost the same. This proved that the membrane itself remained structurally intact. The “holes” (ion channels) were so tiny and specific that they didn’t destroy the overall structure of the cell’s membrane.

Perhaps the most important contribution to the future of the field was Kenneth Cole’s development of the Voltage Clamp technique. In a normal nerve, voltage and current change simultaneously and very fast, making it impossible to study one without the other interfering. Cole’s device used a “feedback loop” to hold (clamp) the membrane at a specific voltage chosen by the scientist. By holding voltage steady, he could measure the resulting flow of ions (current) over time. Cole showed this technique to Alan Hodgkin during a visit. Hodgkin and Huxley then refined it to produce their famous equations.

Cole and Curtis are well known in textbook history for the Cole-Cole plot. This is a mathematical way of graphing how biological tissues respond to alternating currents. It is still used today in Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis.

References:

Finkelstein G (2015) Mechanical neuroscience: Emil du Bois-Reymond’s innovations in theory and practice. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9:133. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00133

De Palma, A., & Pareti, G. (2011). Bernstein’s long path to membrane theory: radical change and conservation in nineteenth-century German electrophysiology. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences, 20(4), 306-337.

Carmeliet, Edward. (2019) “From Bernstein’s rheotome to Neher‐Sakmann’s patch electrode. The action potential.” Physiological Reports 7.1 (2019): e13861.

Hille, B. (2025). A brief history of nerve action potentials after 1600. Molecular Pharmacology, 107(2), 100012.

Narahashi T, Moore JW, Scott WR (1964) Tetrodotoxin blockage of sodium conductance increase in lobster giant axons. J Gen Physiol 47:965–974

Verkhratsky, A., & Parpura, V. (2014). History of electrophysiology and the patch clamp. In Patch-clamp methods and protocols (pp. 1-19). New York, NY: Springer New York.